Gary Staab, Staab Studios

Gary has learned to combine his passion with art and claims, “I’m still in love with Lucy.”

An Artist Interview

created for Best of Artist’s and Artisans web site

By Bridgette Mongeon © 2007

It is wonderful to be able to mix your passion and your art. Gary Staab of Staab Studios has not only accomplished that, but he has also learned how to make a living doing so. Gary’s passions are art, biology, and natural science. He was first introduced to the concept of combining his passions in a liberal arts college when the class was drawing a diorama at the local museum. It struck him that someone had to prepare the exhibits.

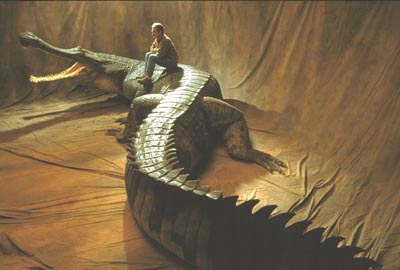

He states, “I always liked making stuff,” and turned his Hastings College studies into a directed study with a focus on art and biology. Soon Gary began to learn from the best at the Smithsonian Institute and the British Museum of Natural History. His work spans sculpting a flea to a T-rex and everything in between. Each project that comes through his studio is different and offers a new challenge. Most of his works are one of a kind, and many of the works, even the very large ones like the 40 foot Sarcosuchus imperator, or super croc that lived 110 million years ago are part of traveling exhibits and must be made to be disassembled and reassembled—seamlessly.

When asked what his favorite sculpture is, Gary is like most artists combing through their mind for the personal connection, weighing each creation, but he found himself drawn to his most recent creative endeavor. “I’m still in love with Lucy,” he states. Lucy, an Australopithecus Afarensis or 3.2 million year old walking primate is part of the traveling exhibit “Lucy’s Legacy”. Gary received a cast of Lucy’s bones and in three months time painstakingly created this wonder of science. He reports that at least a quarter of his time is spent on research, but knows a great deal of his work is interpretation.

“When restoring extinct animals, you can’t be afraid of being wrong.” Gary reports that there are so many scientist and such little material that this has taught him to have a thick skin, to do the best he can, and then trust the one scientist that signs off on the project. He built Lucy from the bones outward and describes forensic art as a science and a rather mechanical process, layering on muscle to a designated point, putting eyes just so. The body came to the artist much easier than Lucy’s portrait bust. As analytical as the process can be he still wants to, “…make it breath as much as I possibly can.” It is when he steps back from the details of the process and realizes it has become real, this is the part he describes as being emotional. “It is a living breathing being, that is the exciting part of restoration.”

Gary has created work for National Geographic Society, the Smithsonian Institute, and Walt Disney animation, as well as a host of others. He has had the privilege of studying fossils, bones, and casts that many paleontologists would love to see. And he is involved in many interesting projects from the Ice Man to the most recent projects in his studio that he wrapped in secrecy. He simply states, “They are two anatomically modern human skulls that are 10,000 years old.” The rest, he reports cannot be discussed.

In his career he has had great adventures such as being invited on archeological digs and measuring crocs in Costa Rica. He spends endless hours studying anatomy and his research also consists of dissection when necessary. The process of creating the super croc documented on the Staab Studio web site states, “To help aid in the understanding of how the musculature system works with the skeletal system, Gary dissected several modern crocodilians.” The study of anatomy is important for restoration, “Knowledge of any living animals compliments the prehistoric,” states Gary.

Each project Gary speaks about appears to be invigorated with a deep respect and a passion. Gary Staab, who for eighteen years has combined his passions for art and science, asks the same question he did when he began, a question that is combined with an infectious, inquisitive nature, “What did this thing look like when it was alive?”